By Lovett H. Weems Jr.

A significant concern within many faith communities in recent years has been the increasing age of clergy in the United States. Such increases in clergy age have been cited since the 1980s. Several reasons are suggested. One is the entrance of second-career clergy. The factor most often identified as the primary reason for the rising clergy age is the aging of the entire population. In recent decades, this trend came primarily from the aging of the baby boom generation (born 1946-1964). Baby boom aging makes a major population impact as the largest generational cohort prior to 2019, when millennials surpassed baby boomers.

Some church leaders fear there will be a clergy shortage as more and more clergy approach retirement age. Others worry about a growing gap between the age of clergy and the age of laity and, even more importantly, between the age of clergy and the general population the church seeks to reach. However, if clergy aging merely mirrors age trends in the larger population, it is then to be expected, and there are fewer options to change the trend. Similarly, if clergy ages match the larger population, there is no appreciable age gap between clergy and constituents about which to worry.

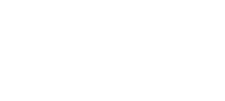

The National Congregations Study (NCS) shows the proportionate decline of solo or senior clergy ages 54 or younger between 1998 and 2018-19. The chart below uses NCS data to track four Christian traditions showing major declines in such clergy, with the greatest decline in clergy under 54 coming among Black Protestants and the least decline among Roman Catholics.

Clergy Aging and Population Aging

According to the NCS reports, among lead pastors of all congregations, the median age increased from 49 years to 57 years between 1998 and 2018-19. Faith Communities Today (FACT), another national survey, found the same median age of 57 in their 2020 study.

Can the aging of the clergy population be explained by the overall aging of the U.S. population? The aging of the large baby boom generation is evident in clergy age trends. But it cannot account for the magnitude of the increase in clergy ages.

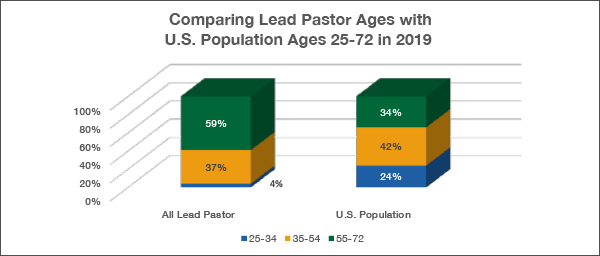

This table shows how the clergy age distribution of lead pastors compared with the age of the total population of the United States, ages 25 through 72, in 2019.

The younger age cohort (34 or younger) is least represented among clergy based on this age group’s 24 percent share of the general population ages 25-72. Only 4 percent of lead pastors are in this age group, far fewer than before in recent decades.

The mid-age cohort (35-54) has declined as a percentage of clergy over the past two decades. It is still closer to mirroring the nation’s population of those between 35 and 54 than is the case for both younger and older clergy age cohorts. While 42 percent of the relevant population falls within this age range, only 37 percent of clergy do so.

Persons between 55 and 72 represented 34 percent of the U.S. population between the ages of 25 and 72 in 2019. This age group reached unprecedented proportions of clergy since 2000. By 2019, 59 percent of lead pastors were in this older age category.

Aging Baby Boomers Provide Only a Partial Answer

The overall aging of the U.S. population led by the aging of the baby boom generation is one factor in the significant aging of clergy. However, these demographic shifts alone do not account for the extent of the high proportion of older clergy and the low proportion of young clergy today.

The challenge for most denominations comes from the dramatic gap between those 25 to 34 in the population and clergy of those ages. Both that large misalignment and the smaller underrepresentation of clergy from the mid-age (35-54) population present a dilemma for many traditions not easily explained by population dynamics.

The dilemma of the aging of clergy leads to some critical questions for churches in the United States. The first is, “What difference does this make for the church?” The alarm as identified by many denominational leaders is the reality that clergy will increasingly be of an older generation than those in the population the church is trying to reach. Does that matter? Some suggest it matters a great deal when there may well be significant generational gaps in culture and perspectives.

Another question emerging from the finding that the aging of the general population cannot account for the extent of aging clergy is, “What, then, might be other factors accounting for the disproportionate aging of clergy compared to the population?” Do church leaders now need to intensify their search for what those factors are and seek to address them? Those troubled by this disproportionate aging of clergy compared to the population might begin by examining the changing makeup of the total population.

Additional dimensions of age demographics may help explain the proportional overrepresentation of older clergy and underrepresentation of younger clergy today. People of color are far more highly represented among the youngest of the U.S. population today, and whites among the oldest. Pew Research shows that the most common age for whites in 2019 was 58. For people of color, it was 27. Immigration has contributed a younger than average population to U.S. demographics in recent decades. The average age of newly arriving immigrants is 31. The extent to which clergy do not mirror the changing population demographics may help explain the underrepresentation of younger clergy.

The disproportionate aging of clergy is a crucial challenge for most traditions. It must be explored, understood, and addressed if the work of the church is to be lived out faithfully.

Lovett H. Weems Jr. is senior consultant at the Lewis Center for Church Leadership, distinguished professor of church leadership emeritus at Wesley Theological Seminary, and author of several books on leadership.

This article was originally published in Leading Ideas from the Lewis Center for Church Leadership of Wesley Theological Seminary.